Gary Taubes paints a lively picture of lawmaker overzealousness, industry subterfuge, and researcher bias to argue that fat may have been unfairly blamed for the ravages of sugar, and as a result, misguided government dietary advice drove Americans to eat more sugar, ultimately contributing to obesity, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. Yet the key questions Taubes raises cannot be evaluated via historical narrative. It’s time to hang up our tweed blazers and slip into our white lab coats, because Taubes has made specific and testable assertions, which I will evaluate in three parts. First, I will examine the 1980 Dietary Guidelines to determine if they condemn fat and take a weak stance on sugar as suggested. Second, I will evaluate the hypothesis that the Guidelines contributed to obesity, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. And third, I will evaluate the hypothesis that sugar “may be the primary cause” of the three aforementioned conditions.

Inside the 1980 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

In the opening sentence of his essay, Taubes states that “forty years ago this month, January 1977, the federal government entered the business of giving dietary advice,” referring to a congressional report that gave rise to the 1980 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. In fact, the federal government has been issuing dietary advice regularly for over a century.[1] The 1980 Guidelines were, however, notable for the fact that they abandoned the traditional “eat more” approach of diversifying and balancing the diet, in favor of an “eat less” approach of limiting foods perceived as unhealthy.[2]

Taubes argues that this document condemned fat and took a weak stance on sugar. Let’s have a look for ourselves.[3] At the core of the 1980 Guidelines were seven pieces of dietary advice, shown below:

As you can see, “avoid too much fat” and “avoid too much sugar” are equally prominent and identically worded recommendations. Taubes suggests that the statement “avoid too much sugar” is vague and lacks conviction—it is “a tautological statement that could apply to any food.” Yet we are intended to believe that the same language applied to fat altered the course of the American diet.

The Guidelines went further, providing explicit guidance on how to “avoid too much sugar”:

- Use less of all sugars, including white sugar, brown sugar, raw sugar, honey, and syrups.

- Eat less of foods containing these sugars, such as candy, soft drinks, ice cream, cakes, cookies.

In the section titled “Maintain Ideal Weight,” the document lays out its four-part plan for weight loss: Increase physical activity, eat less fat and fatty foods, eat less sugar and sweets, and avoid too much alcohol. Again, the advice to limit fat and sugar intake receive equal attention, and the Guidelines clearly implicate excess sugar intake in obesity.

A person who faithfully adhered to the Guidelines would end up eating a diverse, largely unprocessed diet composed of whole grains, beans, nuts, lean meats, seafood, dairy, eggs, vegetables, and fruits, with little added sugar, added fat, or highly processed foods or beverages. Are we really to believe that this advice—which clearly and repeatedly recommended eating less sugar—made Americans eat more sugar, leading to obesity, diabetes, and coronary heart disease? Having reviewed the Guidelines, the notion strains credulity, but let’s test it anyway.

Wrath of the Guidelines

Taubes argues that the Guidelines may have unintentionally contributed to obesity, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. This rests on the assumption that the Guidelinesthemselves substantially influenced American eating behavior, either directly or indirectly via the food industry, and therefore that changes in the American diet over time can be attributed to it rather than to the numerous other shifts in the American food and cultural landscape that were happening at the time.[4] No evidence is presented to support this assumption, so we will examine it here.

If the Guidelines substantially influenced the American diet, then we should observe that total fat, added fat, and added sugar intake declined in its wake. In perfect contrast to this prediction, our total intake of fat remained approximately the same after the Guidelines, our intake of added fat increased, and our intake of added sugar increased.[5],[6]

Furthermore, we should observe a decline in the consumption of highly processed foods rich in fat and sugar that the Guidelines clearly advised against. To test this prediction, here are the top six sources of calories in the U.S. diet, in descending order of importance, as of 2006:

- Grain-based desserts (cakes, cookies, donuts, pies, and related items)

- Yeast breads

- Chicken and chicken-mixed dishes

- Soda, energy drinks, and sports drinks

- Pizza

- Alcoholic beverages[7]

This list is both disturbing and informative. Cake and related desserts are the number one source of calories in the American diet. Soda, pizza, and alcohol are three of the remaining five items. The average American diet is not even remotely inspired by the Guidelines.

The truth is that we don’t wash down our pizza and cake with beer and soda because we think it’s healthy or because we believe the government recommended it. We do it because we are human beings who are driven by considerations of pleasure, cost, and convenience—precisely the qualities the food industry has been optimizing for the last 40 years.[8]

Taubes assumes that we suffer from increasing rates of obesity and diabetes because we have failed to identify their true cause. Yet the evidence suggests a simpler and more compelling explanation: We eat too much food that is obviously unhealthy, and it’s not because researchers or the government told us to, but because we like it.

A Slow-Acting Toxin

According to Taubes, sugar may be a “toxin” and “the primary cause of diabetes, independent of its calories, and perhaps of obesity as well.” Elsewhere in the essay, coronary heart disease is added to the list. Yet Taubes asserts that this speculative hypothesis cannot currently be tested because there is so little existing research on sugar, and so little interest in conducting such research, that “the research necessary to nail it down would take years to decades to complete and is not even on the radar screen of the funding agencies.”

This belief is remarkable in light of the fact that a Google Scholar search returns hundreds of scientific papers on the health impacts of sugar, many of them human randomized controlled trials, and many funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. In reality, the health impacts of sugar are of considerable interest to the scientific community, and as such, they have been studied extensively. Having established that this research exists, let’s take a look at it.

The hypothesis that sugar is the primary cause of coronary heart disease is easily refuted. In the United States, coronary heart disease mortality has plummeted by more than 60 percent over the last half century, despite a 16 percent increase in added sugar intake.[9]Roughly half of this decline can be attributed to better medical care, while the other half is attributed to underlying drivers of disease such as lower cholesterol and blood pressure levels and an impressive drop in cigarette use.[10]This striking inverse relationship is incompatible with the hypothesis that sugar is the primary cause of coronary heart disease, although it doesn’t exonerate sugar.

Is sugar the primary cause of diabetes, “independent of its calories”? Research suggests that a high intake of refined sugar may increase diabetes risk, in large part via its ability to increase calorie intake and body fatness, but it is unlikely to be the primary cause.[11] An immense amount of research, including several large multi-year randomized controlled trials, demonstrates beyond reasonable doubt that the primary causes of common (type 2) diabetes are excess body fat, insufficient physical activity, and genetic susceptibility factors.[12]

The ultimate test of the hypothesis that sugar is the primary cause of obesity and diabetes would be to recruit a large number of people—perhaps even an entire country—and cut their sugar intake for a long time, ideally more than a decade. If the hypothesis is correct, rates of obesity and diabetes should start to decline, or at the very least stop increasing. Yet this experiment is far too ambitious to conduct.

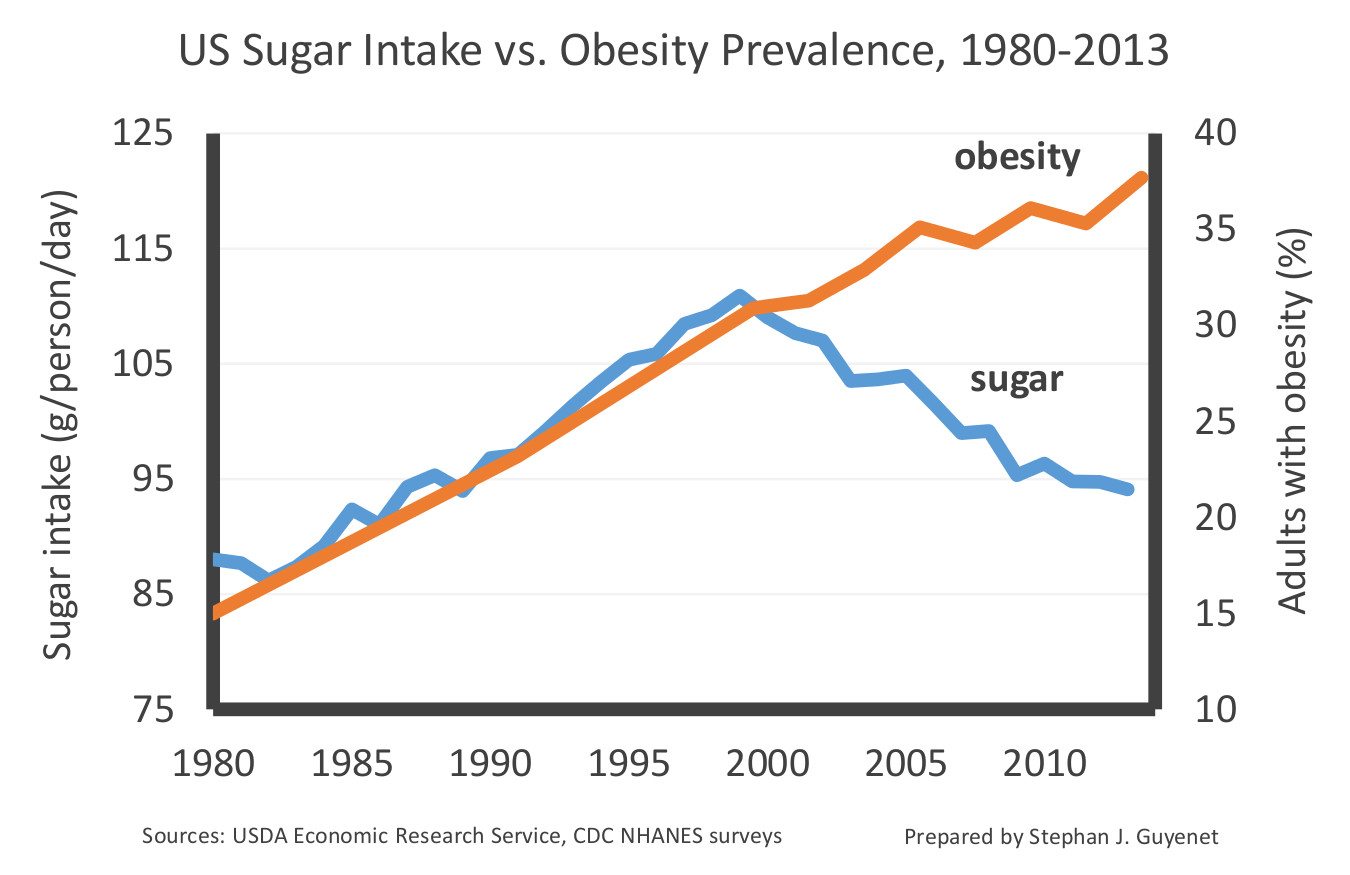

Or is it? In fact, this experiment has already been conducted—in our very own country. Between 1999 and 2013, intake of added sugar declined by 18 percent, taking us back to our 1987 level of intake. Total carbohydrate intake declined as well.[13] Over that same period of time, the prevalence of adult obesity surged from 31 percent to 38 percent, and the prevalence of diabetes also increased.[14]

U.S. sugar intake and adult obesity prevalence, 1980-2013. Data are from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NHANES surveys and USDA Economic Research Service food disappearance records (5,6). Axes are bounded to illustrate correlation, or lack thereof.

Americans have been reining in our sugar intake for more than fourteen years, and not only has it failed to slim us down, it hasn’t even stopped us from gaining additional weight. This suggests that sugar is highly unlikely to be the primary cause of obesity or diabetes in the United States, although again it doesn’t exonerate sugar. Furthermore, it suggests that the laser-like focus on sugar is a distraction from the true, more complex nature of the problem.

I have presented a small piece of a large body of evidence that is more than sufficient to refute the assertion that sugar may be the primary cause of obesity, diabetes, and coronary heart disease. At the same time, this evidence does suggest that added sugar is part of a broader diet and lifestyle landscape that contributes to these three conditions, a conclusion that is not especially controversial within today’s scientific, medical, and public health communities.

No comments:

Post a Comment